Born in Butte, Montana in 1926, Rudy Autio is considered one of the most significant and inspirational artists who worked with clay in the United States today. Rudy Autio headed the ceramics department at the University of Montana for twenty-eight years. He was also a founding resident artist at the Archie Bray Ceramics Foundation in Helena, Montana. Autio received a Tiffany Award in Crafts in 1963, the American Ceramic Society Art Award in 1978, and a National Endowment for the Arts grant in 1980, enabling him to work and lecture at the Arabia Porcelain Factory and the Applied Arts University in Helsinki, Finland. In 1981 he was the first recipient of the Governor’s Award, naming him an outstanding visual artist in the state of Montana. He is a Fellow of the American Crafts Council, an Honorary Member of the National Council of Education in the Ceramic Arts, and, in 1999, he was awarded the American Craftsman’s Gold Medal Award.

While noting some of the influences that shaped his artistic development, it was Autio’s distinctive approach to sculpture in both construction and imagery that cemented his career. Beginning with a sturdy, hollow, ceramic trunk, Autio added ear-like appendages or “cactus arm” extensions, each rounded and smoothed at the join to form subtle, curved transitions. Trained in drawing and painting from an early age, Autio skillfully applied “floating” figures, mainly nudes and horses, to the completed form. There is a certain tension created between the contours of the piece and the outlined bodies. On the other hand, the subtle blending of the structure’s shape and the figurative silhouettes unifies each piece.

From LaMar Harrington’s oral history interview with Rudy Autio for the Archives of American Art’s Northwest Oral History Project, now part of the Smithsonian Institution’s Online Virtual Archives:

I don’t think that the curator of the exhibition is that familiar with ceramics. For one thing, pieces are very low and you’re looking inside these as though they were soup bowls, you know, and this kind of work has to be on an eye level where it can be seen . . . . They need someone who has dealt with clay before, and who has a feeling for it. You don’t put vessels that you’re going to walk around, you don’t ram them up against the wall, if you can help it. To a certain extent you might have to do that, but they certainly ought to be on a visual level–that’s fundamental for sculpture.

-Rudy Autio, describing a recent exhibition during the oral history interview

Audio hit the nail on the head. It is that exact nature, the ability to inspect a piece from countless vantage points as you move around it, that makes sculpture so exciting. Each change in perspective calls for a fresh examination. There is a uniqueness in Autio’s three-dimensional approach and the importance of his choice to work with clay. His constructions illustrate the advantage of using an additive material, such as ceramics, over using a subtractive material, such as wood or stone.

Growing up in Montana, Autio had little opportunity to visit galleries or museums. Direct knowledge came in the form of familiarity with Charles Russell (1864-1926), famous for painting narratives of cowboy and Indian activities, and from after-school drawing classes conducted by artists hired through the Works Progress Administration. The majority of Autio’s knowledge of world art came from picture books or magazines. After attending graduate school at Washington State University, Autio returned to Montana. It is noteworthy that even in his relatively insulated situation, or maybe because of it, Autio’s artistic endeavors were influenced by many disparate factors. Among these factors was the inspiration of long-time Montana friend and fellow ceramic artist Peter Voulkos, who was a leading personality in the “clay revolution” of the 1950s and 1960s, and another lesser-known Montana painter, Henry Meloy. International influences included sculptors Carl Milles and Henry Moore; painters Henri Matisse and Pablo Picasso, who also produced ceramics; ceramicist and designer Isamu Noguchi; and Japanese printmaker Shiko Munakata.

An especially important part of Rudy Autio’s story is his association with the Archie Bray Foundation in Helena, Montana. After their first year of graduate school, Autio and Voulkos took summer jobs at a brickyard owned by Archie Bray, a man whose fondest dream was to found an art center on his company property. It was thought that a pottery would be a good first step toward fulfilling this vision. After a full day of labor at the brickyard, Autio, Voulkos, and other volunteers would work additional hours, constructing a building where pottery production and sales could take place. They also built special down-draft, gas-fired kilns. At the same time Autio and Voulkos began to produce their own work, and, after finishing graduate school, both potters returned to the Bray to become the first resident artists. Autio continued in this position at the Bray until 1957, executing a number of large architectural commissions during that time. Though one might characterize the Bray as “remote,” it was not isolated. Visiting artists, including Bernard Leach, Shoji Hamada, Rex Mason, Tony Prieto, and Carlton Ball, came from all over the world. The Archie Bray Foundation remains to this day a most prestigious school and arguably the best and most elite institution for ceramics in the country. Today, artists from China, Russia, Japan, Central America, Korea, Africa, and many other countries continue to visit, work, and study at the Bray.

Not long after leaving the Bray, Autio was hired as a ceramics instructor by the University of Montana in Missoula, where he taught for 28 years. In 1963–64, Rudy took a leave of absence, traveling to Italy with his young family to visit and see first-hand the great antiquities of the Renaissance in Florence and the Vatican. That same year, the family also spent a few months in Brooklyn, where Autio was able to immerse himself in the big city activities of New York. Upon his return to Missoula, he drew on these experiences to work with newfound eagerness, ideas, and images. Though the demands of academia were always great, Autio built bridges to the national and international clay community through the more than 150 ceramic workshops in which he participated. The most prestigious of these was perhaps Supermud, held annually at Penn State for a twelve-year period from 1967 to 1979, featuring such artists as Jun Kaneko, Robert Turner, Don Reitz, Robert Arneson, and many others now grandfathered into the pages of twentieth century American Ceramics. Autio pointed out that as a result of his active participation in these national and international workshops, he was far from isolated and had opportunity to visit both urban and rural areas, co-mingling with other ceramic artists throughout the world. Most importantly, these workshops enabled a transfer of energy and enthusiasm between Autio and his audience and vice versa.

In 1981, Rudy Autio was awarded a grant by the National Endowment for the Arts which he used for travel to Finland, the birthplace of his parents. Taking a leave from the University, Autio arranged through Tapio Yli-Viikari, head of the design department at the Arabia Porcelain Factory, to work there as a studio artist. Autio had the experience of a lifetime, working with the provided materials and equipment: porcelain clays, colored slips, and technical support. During this time, Autio found a new way of working and an appreciation for a color palette previously unknown to him. According to Autio’s wife Lela, “Rudy’s experience at Arabia compelled him to work with more color” and led to “more refinement in the drawing and more attention to the synthesis of drawing and form,” which “develops more of a narrative.” The entire experience made Autio long to return to Finland, a desire that was fulfilled more than once after his retirement from the University of Montana in 1984.

Retirement afforded Autio the luxury of time to concentrate on creating his own body of work and even more opportunity to travel. Workshops and commissions took him to Helsinki, Tokyo, Korea, Oslo, Ringebu (in Norway), and Korea. He visited Japan three times as a juror of the international show at Mino and as an invited artist at Shigaraki. His experiences there included a commissioned work in Tokyo, presentations at Nagoya, the Aichi Museum, and dozens of visits around Japan, including an introduction to the well-known kilnbuilder Yukio Yamamoto in Himeji.

Connection to his native Montana remained strong. Autio was born there, put down deep roots, and spent virtually his entire life there. Asked about this choice, he said, “it is true that Montana is still somewhat isolated, but I have never felt isolated from the world of art.” Workshops, visitors to the Bray, and membership in the International Academy of Ceramics provided a community of good friends from all over the world.

Rudy Autio passed away from leukemia in 2007.

-from the American Museum of Ceramic Arts (AMOCA) biography on Rudy Autio

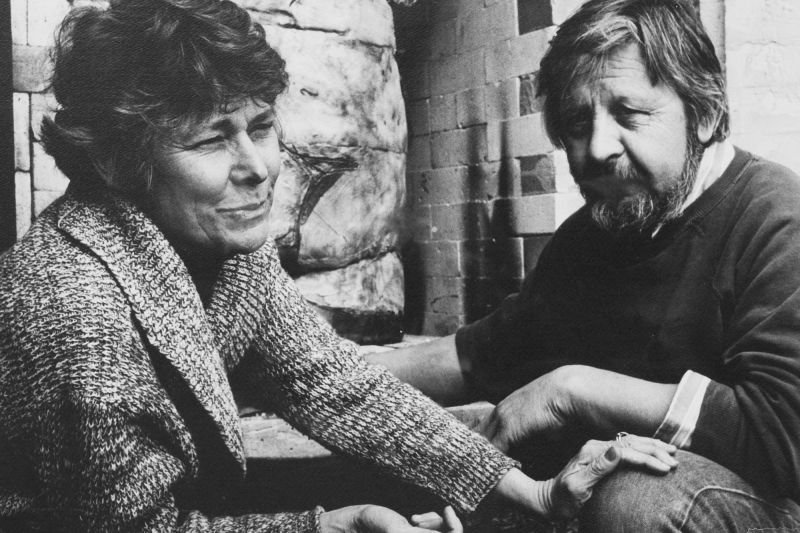

Rudy working on one of his last 6 large pots at Archie Bray Foundation, 2006. He died the next year, June 2007.